What is different about the Saint George Albrecht Altdorfer portrays in his masterpiece?

- Teutonic tales vs. Roman stories

- Loneliness, relief, and looming trees

- Humility and a fresh take on victory

Click here for the podcast version of this post.

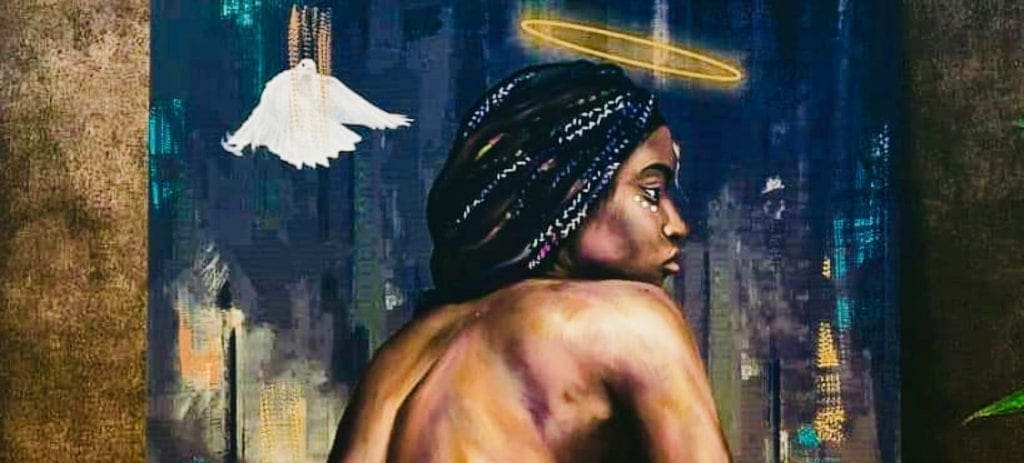

Saint George has already killed the dragon in Albrecht Altdorfer’s painting. The monster kneels before him, vanquished. This beast looks up at the knight in agony. It’s over. Altdorfer has ended the story before it’s even begun for us. With this choice of scene, the painter brings our attention to setting rather than story. Viewers see more of a statue than a scene between St. George and the dragon. It’s not a painting about these subjects. The forest itself matters most here.

It’s a Teutonic take on the classic Saint George dragon story. Germans obsess over the forest. That’s because of the Black Forest. It’s been a source of deep mystery and inspiration to the German culture since antiquity. Altdorfer’s Saint George works as the Grimm’s fairy tale of paintings. It’s the Black Forest cake of the art world. These Teutonic cultural icons exemplify the rich wonder and awe of dark woods.

If you’ve ever read a Grimm’s fairy tale, these woods sound familiar. They seem scary. And a bite of the rich, dark, cake doesn’t make the Black Forest seem safer. This isn’t like any other children’s story or chocolate cake. It’s deeper and a bit darker. Saint George by Albrecht Altdorfer brings us that same experience in another format. The dragon dies alone. Only his enemy, St George, stands nearby. These three figures seem to drown in the thick forest, though. We only notice them because of the painting title. It forces viewers to squint at the scene and try to identify the saint and his victim.

Where’s the Dragon in Albrecht Altdorfer’s Saint George?

Altdorfer’s Saint George portrayal isn’t like any other. That’s because dragons bring such sexy mystery to any story. Artists love to paint their thrilling danger and enchanting bodies. But Altdorfer deflates this dragon. It’s a challenge to even see among all the lush forestry. Infinite woods create the mystery rather than a mythical creature. Saint George already slayed that part of the fantasy. It’s a unique and humble take on a familiar, old, story. Altdorfer gives us a private moment. Traditional Roman storytellers focused on this tale’s pageantry.

This painter chooses a less flashy scene. Still, it entrances viewers with the Black Forest’s deep secrets. We see the lone knight bent forward on his white horse. He looks bereft, head down and away from us. Looming masses of trees stand in for the audience we see in most Saint George paintings. There’s not even a princess to save or impress. That’s usually his whole motivation. In the typical Roman version of this story, George kills the dragon to save the princess. It’s a fairy tale. But there aren’t any such fantasies in the Black Forest. We’re in the land of the lonely.

Altdorfer hints at this with the title. Most Saint George paintings feature the dragon. These traditional portrayals relish the gorgeous ferocity of this monster. The beautiful beast terrifies us. That makes Saint George seem all the more heroic. These dragon-centric paintings include the monster in their titles as well. Altdorfer leaves the dragon out of his painting title. The knight is alone even there. It’s a painting about isolation. But even more important, it sends us a message about integrity. We see the truth of a person when they’re alone. Here George slays the dragon to save himself – but also the rest of the world.

After all, riding the horse, he could have fled to avoid a confrontation. Rather, Saint George chose to face the dragon and end this danger to his people. Nobody was there to cheer, clap, or even thank him. An audience of only trees and silence surround the scene instead. This setting gives the painting a profound air of peace. We can sense the relief and residual sadness after battle. Saint George shares such a humble point of view on victory. The knight doesn’t raise his sword to the sky in that clichéd, macho, symbol of triumph. This saint reads as vulnerable and pensive. His horse, no mighty steed, seems still afraid of the dragon. He’s got no need for showy sweeps of splendor. That’s what makes him a saint.

This German Saint George needed no glory. He only wanted to do what was right. In the Black Forest this mere man becomes immortal thanks to this heroic act. Placing him alone among the woods, Altdorfer seems to say that the trees tell us this tale. The forest holds many secrets; tells even more stories. Here the woods whisper this modest knight’s story to us with a quiet, gentle, majesty to match his manner.

We also catch a tiny glimpse of the world outside the forest at an open space in the bottom right. There Altdorfer gave us a lens into the land far beyond this scene. That’s where the story of Saint George will live on through the ages. It’s a distant window into the human world that reminds us of the other lives saved by George’s heroic act.

Saint George (in the Florest) – FAQs

When did Albrecht Altdorfer paint Saint George (in the Forest)?

This masterpiece in oil on parchment dates back to 1510. Saint George (in the Forest) lives at the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, Germany. It’s a fitting home for this old painting of a legendary story. That’s because the Alte Pinakothek is one of the oldest art galleries in the world.

In fact, Alte means “old”. But the museum is much younger than Albrecht Altdorfer’s masterpiece. The Germans first established this collection in 1836. It’s called Alte because it holds artwork that spans the 14th through 18th centuries.

Why is Saint George by Albrecht Altdorfer an important artwork?

Albrecht Altdorfer clearly loved the story of Saint George. His 1510 masterwork in oil shows his fondness for the humble hero knight. It also portrays nature’s power over man with an overwhelming setting of a lush and enigmatic forest.

We know this artwork wasn’t a mere whim for Altdorfer because he created another Saint George. In 1511, right after this painting, he portrayed the dragon slayer yet again. This time it was in woodcut (shown at right). There are parallels to the painting. For instance, both depict only the knight, horse and dragon. No princess or audience are shown. The duo also show the same moment, after the dragon was slain.

But Altdorfer’s woodcut lacks the Black Forest wonders of the 1510 Saint George. Instead, he carved looming mountains with a castle perched upon one of them.

ENJOYED THIS Saint George ANALYSIS?

Check out these other essays on German Painters

Wood, Christopher S. (1993). Albrecht Altdorfer and the Origins of Landscape. Reaktion BooksWood, Christopher S. (1993). Albrecht Altdorfer and the Origins of Landscape. Reaktion Books

Alte Pinakothek. Summary Catalogue. Edition Lipp, 1986.

Visit the Alte Pinakothek website

Stefano Zuffi , Il Cinquecento, Electa, Milan, 2005

Anita Albus, Die Kunst der Künste. Erinnerungen an die Malerei, Eichborn Verlag, 1997

Check out this Online Archive of Albrecht Altdorfer paintings

Christoph Wagner, Oliver Jehle (eds.), Albrecht Altdorfer. Kunst als zweite Natur, 2012, Schnell & Steiner Verlag, Regensburg

Jochen Sander, Stefan Roller, Sabine Haag, Guido Messling (eds.): Fantastische Welten. Albrecht Altdorfer und das Expressive in der Kunst um 1500. Hirmer, Munich 2014