New Yorkers know the name Dyckman. But many aren’t aware that this notoriety began with a tract of land and simple farmhouse. Luckily, it still endures as a vital, engaging museum in Upper Manhattan. This brings its complicated history into the present day. In fact, The Dyckman Farmhouse Museum bursts with relevant surprises. Resident Artist work illuminates the site’s history with insight and keen detail. This includes refreshing honesty about slavery in Dyckman history.

For an audio version of this post, click here:

The backyard’s packed with points of interest as well. A Dyckman Farmhouse ancestral cherry tree arches overhead. It’s relative to an original from their 1784 orchard. Also, a Hessian Hut lies within the side of a tiny hill, only a staircase away. This area also sets stage for many community events. There’s planting, harvesting, cooking, and more. The Dyckman Farmhouse Museum staff keeps these activities real and relevant with native lenape crops.

Best thing about Dyckman Farmhouse Museum lies in this play between past and present. The family’s impact resonates with more than a subway stop and street name. It’s no wonder. At one point the family farm covered most of upper Manhattan. Such a vast Dyckman lot’s pretty ironic, though. That’s because at one point fourteen kids stayed in the tiny upstairs area. Cramped quarters always seem to define NYC, even in this prosperous family.

Dyckman Farmhouse History

The name Dyckman signifies “New Amsterdam” for good reason. After all, Jan Dyckman came to Manhattan in the 1660s. Apparently, his waistcoats were stuffed with cash. He purchased large lots of land around what’s now 207th street. Thus, today we get off the train at Broadway and 207th to greet the Dyckman Street Station. Jan’s original lots of land sat astride the Nagle family’s large land holdings. So, the Dyckmans used the same strategy uptown that the Lefferts did in Brooklyn. They married into the Nagle family and thus doubled their property. By the time of the Revolutionary War, if venturing far uptown, you stood upon Dyckman land.

The current Dyckman Farmhouse wasn’t built until after the war, though. Revolution torched upper Manhattan. Jan’s grandson William Dyckman returned home after British evacuation to mere ashes and memories. Determined to prevail, he then started over. Step one, the Dyckmans constructed that current farmhouse. This stayed in the family until they sold it in 1871.

Forty four years passed with the house serving as a rental property and inn. But not to fret, Dyckman resilience soon triumphed. In 1915 Mary Alice Dyckman Dean and Fannie Frederika Dyckman Welch bought the landmark. Wed to an architect and Dean of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, they were well-suited to the project. This family team crafted a lasting and poignant museum. Dyckman Farmhouse thus continues to serve the public in perpetuity.

Thanks to this historic museum, we’re still uncovering the Dyckman impact on New York City. In fact, the farm’s art program shines a Dyckman brand spotlight even beyond that. Their Ground Revision exhibit explores power and the powerless in the community. It focuses on the Inwood slave burial ground. This desecrated grave site lies near the farmhouse under a school parking lot. Discovered years before, this burial ground remains a sacred secret. It’s been kept from too many and for far too long.

Artist in Residence

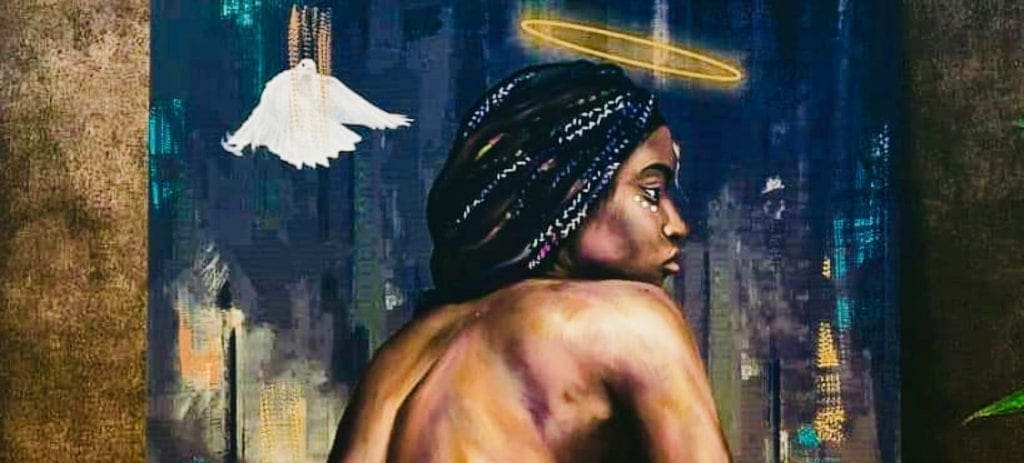

Peter Hoffmeister creates poignant art to provoke fresh perspectives on Dyckman History. His work Ground Revision illuminates the family story for today. It’s no longer the legacy of only white landowners. After all, along with most of upper manhattan, the Dyckmans owned slaves. The family had to bury them somewhere. But no records of these burials exist. Then, in 1903 construction workers discovered an enslaved African burial ground. Their Inwood location indicates the remains were likely residents of the Dyckman Farmhouse community. Even in burial, these people got the shaft. Not even a marker to show they mattered.

Authorities again dismissed them in 1903. That was when their remains got tossed without record. This horrific act marks the intersection between past and present. These people served as slaves – oppressed in life. Their remains were tossed away without regard after death. In this way the Inwood African burial ground spotlights power and the people it crushes. They paved-over this desecrated graveyard in 1903. It remains unsanctified even today – a cement lot where children play. That’s why this area needs a historic site marker.

Hoffmeister’s art grapples with this dynamic between power and the oppressed in history. But it also highlights how secrets hold their own power. The truth comes out. Even buried deep under gravel, dirt and pavement, one day it sees the light. The Ground Revision exhibit points to these significant historic truths. Check out the video below for just one such example. Then visit Dyckman farmhouse Museum and see the entire exhibit. It’s thoughtful, illuminating, and an inspiration.

Historic House Trust Matters

Thanks to my partnership with Historic House Trust of NYC, my visit was a private delight. Dyckman Farmhouse Museum art, events and stories are invigorating. They inspire me to learn more. In fact, I can’t wait to visit again and see the ancestral cherry tree in full bloom.

I’m also excited to see all 23 of HHT’s historic home sites across NYC’s 5 boroughs. Travel 367 years of history right along with me! Visit Historic House Trust on their website.